There are very few wooden block planes out there. This is partially because it is challenging to make a wooden block plane with a low bedding angle. One of the few available today is from German manufacturer E.C.Emmerich, (E.C.E.) founded in Remscheid, Germany in 1852. E.C.E. are well known for making a unique series of wooden planes with blade adjustment mechanisms. Whilst not as prominent in North America, the use of wooden planes is still common in mainland Europe.

E.C.E. make one block plane. While not a true block plane, it is pretty close, and is good at planing grainy wood. The 649-P “POCKET” block plane is a 6-inch plane with a body made of hornbeam and a sole made of lignum vitae. The blade is 1½” in width, and bedded at 50º. The lignum vitae sole of the plane is attached to the body using an intricate bi-directional finger joint. Lignum vitae is the ideal sole for a wooden plane because it is heavy, and dense, and as such will attract very little wear. It is also naturally oily, thereby producing less friction during cutting, and making the use of wax on the sole unnecessary.

The body of the plane is made of hornbeam, an extremely hard wood sometimes known as ironwood. Hornbeam (European) is quite unique to the usual use of beech in wooden planes, and has a slightly higher Janka hardness (1630). The most interesting thing about this plane is the blade adjustment mechanism. Its lever cap is a simple aluminum one which is attached to the body of the plane with two wood screws which pass through holes in the blade. Note that this, unlike most other block planes is a bevel-down plane. The blade is bedded at 50º (York pitch), meaning that it is ideally suited for use on hardwoods, or woods that have highly figured grain. The blade can be adjusted without loosening tension so small adjustments can be easily made.

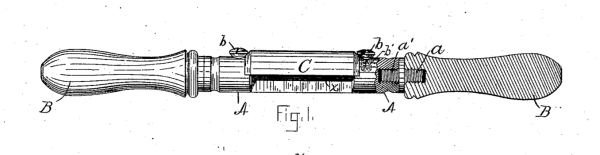

The blade adjustment mechanism, used for depth adjustment is installed in a cavity in the body, thus allowing the bed of the plane to maintain its dampening effect on the blade (reducing chatter). The mechanism itself is a simple threaded assembly with a carriage and pin that engages a hole in the blade. The blade is adjusted by moving the mushroom-like adjustment knob attached to the thread. Moving it clockwise extends the blade below the sole, counterclockwise backs the blade off. This knob has the dual purpose of a palm-rest whilst planing. The negative with this set-up is the potential to inadvertently change the depth setting of the blade by rotating your palm, however there is 1/3 of a turn of give before the cap engages the screw in either direction.

Lateral adjustment can be achieved by grasping the iron at the top near the adjustment knob and pushing it left or right as required to make the edge of the cutting edge parallel with the sole. Finer adjustments can be achieved using a plane hammer. This plane originally had a traditional wood-wedge to position the blade, and wooden palm rest at the back of the plane. Beyond that little has changed.