The second reason the use of wooden planes declined is the introduction of metal planes. On August 24, 1827, a patent was assigned to Hazard Knowles of Colchester, Connecticut, for “Plane stocks of cast iron“. This is the earliest known patent, but of course this doesn’t preclude other metal planes having been invented at an earlier time.

Patent No.4859X (1827)

This one patent in itself did not lead to an overnight demise of wooden planes, but it did contribute to an evolution of metal plane patents. (There is a possibility that there were more patents related to iron planes, but an 1836 fire in the Patent Office, resulted in only 2,845 patents being saved – all patents with an X are pre-1836).

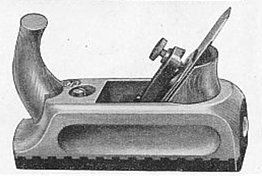

Some of the benefits of metal planes over their wooden brethren was the fact that cast iron provided a more wear resistant sole than wood, but even more important were the improvements in the alignment and adjustment of blades. It is much more difficult to maintain consistency using a wooden wedge to hold the iron in a wooden plane. A patent by William S. Loughborough in 1854, furthered the cause. This patent (No.10,748) described a means of fastening the blade on a metal plane, touting the benefit of being able to easily adjust the throat opening.

Patent No.10,748 (1854)

The patent of 1859 (No.23,928) was for an improved bench plane (actually looks more like a skew-smoother), and described the idea of a screw to maintain the lever cap, and an adjustable parallel fence. The Loughborough was manufactured by George and John Telford. Their ad (1867) below shows plow, filister, and smoother planes.

New York State Business Directory (1867)

Telford did not survive beyond the late 1860s. The Metallic Plane Co. of Auburn NY, manufactured places from 1867-1880. In an advertisement for PERFECT METAL PLANES, by E.G. Storke in 1870, the virtues of the metal plane were extolled.

“Perfect Metal Planes

Have long been sought, and are at length made, and prove a great BOON to WOOD-WORKERS. They are light, CHEAP, and durable. Work very EASILY and PERFECTLY on hard, soft or eaty timber, or on end-wood, and are very convenient. The CUTTING IRONS, now generally so poor, are, by us, all WARRANTED SUPER-EXCELLENT, TRY THEM.”

None of these small companies lasted long, but that was probably due to an inability to advertise the benefits of their product, rather than a deficient product. It was to take the larger companies like Sargent and Stanley to usher in the age of the metal plane.