I bought my first Japanese saws from The Japan Woodworker, which in the 1990s was one of the few places you could buy Japanese tools (long before it was absorbed into Woodcraft). Back then the use of Japanese tools wasn’t very common. It seems like California was the epicentre of the Japanese tool trade, as it had not only TJW (Alameda), but also Hida Tool Co. (Berkeley), who provided a cornucopia of tools for new ways of doing things.

The problem was there was very little in the way of instruction. About the only reference to their use was Toshio Odate‘s classic book Japanese Woodworking Tools: Their Tradition, Spirit and Use first published in 1984. It took a while for these tools to catch on to the wider woodworking community, partially due to the ingrained nature of western woodworking. But there was also very little in the way of quality western saws, leaving an opening for Japanese saws to take up the slack. In the 1980s there was very little happening in Western tool revival beyond Lie Nielsen and Veritas.

There is no doubt that most Japanese tools still do not have a wide audience in western woodworking. The reasons are many, but I think it boils down to simplicity. Japanese saws are easy to use, and the same cannot really be said of other Japanese tools. Chisels are often reasonably expensive, and require a bit more knowledge to keep in pristine condition. The planes are fantastic as well, but again need a little more knowledge, and fine-tuning to optimally use.

Another reason is that standard Japanese saws are inexpensive, and although blades cannot typically be resharpened, they can easily be replaced. For the connoisseur of saws, the handmade Japanese saws (which typically have fixed blades) can be resharpened, but these saws are also expensive. It is this affordability that likely has novice woodworkers gravitate towards Japanese saws. Although bespoke western saws are superbly made, they have become expensive (which is not surprising considering the work involved).

Japanese saws are likely the one Japanese tool that has made meaningful inroads into the Western toolbox. This is likely for a number of reasons (in comparison to their Western counterparts):

- Ease of use − Japanese saws cut on the pull-stroke as opposed to Western saws which cut on the push stroke. While it can take a bit of getting use to, it leads to less binding and smoother cuts. Japanese saws can also be used in a multitude of configurations, such as the low Japanese workbenches. In addition many saws can be used in a two-handed configuration providing better management of cuts.

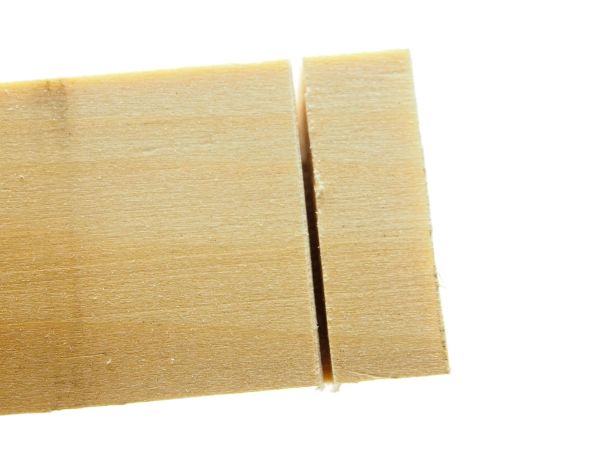

- Thin kerf − The thin kerf, or the slit made by cutting with a saw, means less material is removed, making the process extremely efficient, and requiring less effort than a similarly sized Western saw. Thinner blades means less force is required, providing more accuracy.

- High back − High backs, and a lack of the rigid back of some Western saws (except for Duzoki saws) makes it easy to make deep cuts.

In addition there are specialty saws that often don’t have an equivalent in Western saws. For example Azebiki saws which can be used for cutting sliding dovetails, and grooves mid-panel, or Kugihiki saws which are used for flush cutting dowels.

For the young hobbyist woodworker, Japanese saws are easy to learn how to use, and flexible for use in many situations. The saw basically becomes an extension of the arm, offering many different ways of being used. The one downside is still a lack of literature – while there are books for planing like Discovering Japanese Handplanes (by Scott Wynn), there isn’t much in the way of knowledge surrounding saws. Also the task of choosing the right saw for a particular task can often become quite confusing when you consider the sheer volume of different saws produced by Japanese manufacturers.

Next, we will cover the types of Japanese saws.